Suspected Egyptian militants raise stakes in insurgency

By Michael Georgy and Yasmine Saleh

CAIRO, Feb 17 (Reuters) - The bombing of a tourist bus in Egypt by suspected Muslim militants marks a strategic shift to soft targets that could devastate an economy already reeling from political turmoil.

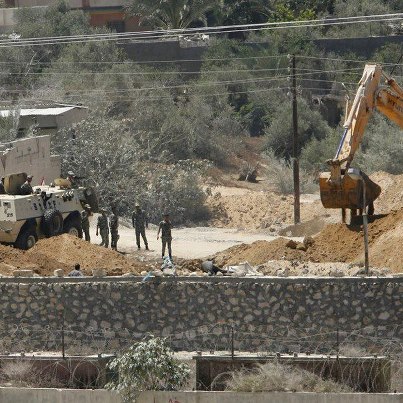

The assailants, who killed two South Koreans and an Egyptian on Sunday, chose their area of operation shrewdly - a poorly guarded buffer zone in the south Sinai between Egypt and Israel.

Although casualties were relatively low, militants know television images of the damaged bus will help deter foreigners and hurt the struggling tourism industry, vital to the economy.

There was no immediate claim of responsibility for the attack, the first on tourists since the army toppled Islamist President Mohamed Mursi in July after mass protests against him.

But suspicion fell on Egypt's most active Islamist militant group, the al Qaeda-inspired Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, which has promised to topple the interim government installed by army chief Field Marshal Abdel Fattah al-Sisi.

Last month the group threatened "an escalation to target the economic interests of the regime", specifically naming a gas pipeline that "brings billions of pounds to Sisi and his generals". Several gas pipelines have been bombed since then.

Based in the largely lawless Sinai peninsula, Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis has intensified attacks, killing hundreds of policemen and soldiers since July and claiming an assassination attempt on the Interior Minister in Cairo.

Last month, a YouTube video purportedly showed an Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis missile attack that downed an army helicopter, killing five soldiers. In the footage, a black-clad militant fires at an aircraft. A voice delivers a warning to Egyptian leaders.

"We tell our big tyrants: isn't it time you learned from what happened to your likes in Libya and Syria and other Muslim states?" said a man identified as Mujahid Abi Osama al-Masri.

Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis is no match for the Arab world's strongest army and may reckon that attacking tourists will hurt the government more than ambushing soldiers, given Egypt's need for tourism dollars to help plug its budget deficit.

The uprising that toppled Hosni Mubarak in 2011 scared off many tourists. Visitors are down to a trickle since Sisi deposed Mursi, ushering in modern Egypt's bloodiest political crisis.

Tourism accounted for more than 10 percent of gross domestic product before the anti-Mubarak revolt.

Anna Boyd, an analyst at London-based IHS Jane's, said militant attacks on tourists had been on the cards for a while.

"DEEP-SEATED RESENTMENT"

"There is a campaign to undermine the state and of course most of that has been to target the military and government assets," she said. "But really to hurt the state you have to go after its sources of revenue, and tourism is part of that."

The bus attack revived memories of an Islamist insurgency in the 1990s. Mubarak took years to crush that campaign, which included the 1997 bloodbath at Luxor, when 58 tourists and four Egyptians were killed at a woman pharaoh's temple.

It may take longer this time. Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis, unlike its militant precursors, is entrenched in Sinai's deserts and mountains, with the support and protection of Bedouin and smugglers long angered by government neglect of the region.

Al Qaeda fighters have also entered the Sinai, exploiting a post-Mubarak security vacuum, analysts and diplomats say.

"The Bedouin population of the Sinai historically has had a tenuous relationship with more fundamentalist strains of Islam," said the Saban Center for Middle East Policy at Brookings.

"Their deep-seated resentment of the government, driven by their stagnating socio-economic circumstances, created a fertile environment for Islamism to gain a foothold."

Given Sinai's remote, rugged terrain, Egypt plans to rely more on intelligence-based attacks to root out militants.

"We will depend...on preemptive strikes," a military source said. "Intelligence will gather information which will be used to strike against the militants before they can make a move."

Ansar Bayt al-Maqdis has become more brazen, extending its reach to Cairo despite military offensives against its hideouts in Sinai, a 61,000 square km (24,000 square mile) region located between Israel, the Gaza Strip and the Suez Canal.

The Sinai is partly demilitarised under the terms of Egypt's 1979 peace treaty with Israel.

Sisi and government leaders often promise Egyptians they will wipe out the militants, but military and security officials privately concede they have no easy task, especially if banks and other businesses become targets, as well as tourists.

"Suicide operations are very hard to prevent," said an army source. "Orders have been given to boost security measures at state economic institutes, banks and government establishments."

Many Egyptians back Sisi, who they expect to run for president and win an election due within months, but some security officials fear the violence might only intensify.

"It is expected that attacks will escalate after Field Marshal Sisi comes to power as militants will then see the whole state as a military-run state," said one security source. (Additional reporting by Shadia Nasralla and Asma Alsharif and Maggie Fick; Writing by Michael Georgy; Editing by Alistair Lyon)

facebook comments